"xiaozu" — Inside Beijing’s Boldest New Art Generation

An experimental art space built by four young artists who dare to begin, without permission, without funding, and without any interest in being “understood.” (video + essay)

Editor’s Note

Growing up in Beijing, I’ve always felt the city’s artistic DNA: complex, shifting, endlessly resilient. When I returned earlier this year, I came across xiaozu, an artist-run space founded by four young artists, including a high schooler who’s already one of the most compelling experimental musicians in the scene. Visiting their space and witnessing their performances was a visceral reminder of how hard, and how vital, it is to simply create in uncertain times.

Now based between New York and Beijing, embedded in the global art ecosystem, I often ask: What gets visibility? What gets funded? What systems shape our sense of value? Xiaozu reminded me that outside the infrastructures we know, raw, urgent acts of imagination still happen, often unrecorded, always at risk.

I commissioned this video and essay not only out of admiration and support, but because I believe in artistic voices that insist on independent thinking. In a city where many spaces are closing, xiaozu is dreaming to grow: searching for a new venue, and aiming to start a residency program. I hope this piece brings their vision into wider view, and helps them build the future they deserve.

The piece closes with William Blake’s poem “The Tyger.” Blake’s tiger is not just a symbol of power, but of the sublime terror of creation; the kind of beauty born from pressure, risk, and refusal. In invoking it, xiaozu aligns itself with that lineage: not of tame spaces, but of fierce, trembling beginnings.

Video: xiaozu- A New Experimental Space in Beijing

Xiaozu Founders: Konini, Xu Chucia, Zhao Xuan, Zhao Ziyi.

Special Thanks: Jeffrey

Filmed by xiaozu in Beijing, 2024- 2025

Article written by xiaozu

一. "Inventing some new works ˮ

September 23, 2024, the Sanyuanqiao (the third ring bridge) pedestrian tunnel in Beijing.

Musician Wang Ziheng kicked a plastic bottle at the camera while playing a giant plastic pipe. Another performer, Hadi Marvian, kicked a soccer ball with the audience in the tunnel.

A man in drag wandered over from the nearby park. ‘It’s dangerous over there,’ he warned — but then added, almost wistfully, ‘It’s been a long time since I’ve seen young people having fun like this in Beijing.’

Wang played the saxophone for him. Nearby, in a carved bamboo basket, two local Chinese wines — kumis (fermented mare milk) and Shaoxing (traditional Chinese yellow rice wine) — were being gently warmed. That day marked the first outdoor performance hosted by Xiaozu, a newly opened artist-run space. It felt almost serendipitous that the phrase “Beijing hasn’t seen something like this in years” lingered over the four young founders, like both a blessing and a curse.

This performance was originally planned to be held at xiaozu’s venue on Gulou West Street in central Beijing, but due to a neighbor’s report a few days earlier, it had to be moved to the underground tunnel. In Chinese, ‘xiaozu gongzuo (小组工作)’ means ‘group work.’ In the context of the space, they hope to “invent some new works through the group format.” One of the co-founders explains, “the word ‘chuangzuo (创作)’ in English is ‘creation,’ which can mean both ‘manual creation’ or ‘artwork creation.’ We were thinking of this place as a creative site, a way to connect artworks closer to the space itself, and present everyone’s work / process in an interesting way.”

Xiaozu’s space turned out to be a really good place to work. The silver iron ceiling on the first floor gives off a sense of coolness and strength. The activities and events are usually organized by small artist groups. People also came here to do everyday tasks like to practice instruments, to draw, to write, and to chat. A few months ago, we also held an open call and formed a more formal creative group, where participants continue to push their work forward through discussion and critique.

Xiaozu is run by four young creatives: Konini, Zhao Ziyi, Xu Chuxia, and Zhao Xuan, ranging in age from 17 to 28. Together, they are responsible for organizing exhibitions, performances, screenings, workshops, and night classes. As a space that claims to “invent some new work,” xiaozu has its own raw vitality. Compared to other spaces located in commercial or arts districts, most events aren’t overly formal or didactic; instead, they blend artists’ personal styles with public participation in hopes of fostering collective happening and exchange. For example, a recent “massage night school” was initiated by an artist currently studying massage therapy, who hoped to develop new creative ideas through learning and practicing together with members.

⼆. Fluid but Unbroken1

At a discussion on alternative art spaces in Beijing co-organized by Stilllife, Sofi Zhang, and Assembly Beijing, xiaozu as a new artist-space representative, was asked: “how do you think about “sustainability?” xiaozu’s response was “we don’t.”

Xiaozu’s response, or rather, the attitude, reflects a generational difference in how Beijing non-profit art spaces approach work and time. Chinese young people who have come of age in an era of rapid changes, including the pandemic period, don’t see sustainability as an expectation or a goal. Xiaozu doesn’t see “the future” as something to aim toward in the same way those who grew up during periods of economic expansion might.

The saying goes, “all that is solid melts into air." You realize that the eternalist self-obsession with permanence has turned into a kind of compulsive hoarding. Adapting to change seems to be the only viable option. And from these fleeting moments, strength can emerge.

This kind of strength can be seen in just about every aspect of xiaozu. For example, unlike other spaces where programming is shaped by a unifying curatorial tone, the four founders of Xiaozu initiate activities independently. Their different aesthetics and interests give the space its eclectic vitality. Different communities intersect here: painters, experimental musicians, performance artists, poets, scholars, and filmmakers. These groups, often kept apart in China’s art world, gradually become entangled at Xiaozu. The boundary between “audience” and “performer” is also blurred — many people give their first ever performance or action here, often they’re awkward and clumsy, but always sincere and endearing.

The four founders, each rooted in different disciplines, also started a band project called “A Weekly Commitment.” They’ve done one performance so far, which was described as having “the energy of China’s early underground punk scene.”

Konini also shared some changes in her own approach to media: “This morning while painting, I suddenly began to hear more sounds, to notice my body... After getting into performance, I’ve come to love its immediacy and how each person has such a distinct physical presence. Now in my painting, I want to preserve that bodily quality — rather than relying on the kind of symbolic language that’s often emphasized in traditional canvas work.”

This sense of fluidity also extends to xiaozu’s exploration of boundaries/limitations. Unlike formal institutions, an alternative space like xiaozu can accommodate projects that are more informal, speculative, or rooted in everyday culture. For instance, we once hosted an exhibition on the printing process of traditional Chinese joss paper — ritual currency burned for the dead — a subject unable to be explored in institutional settings.

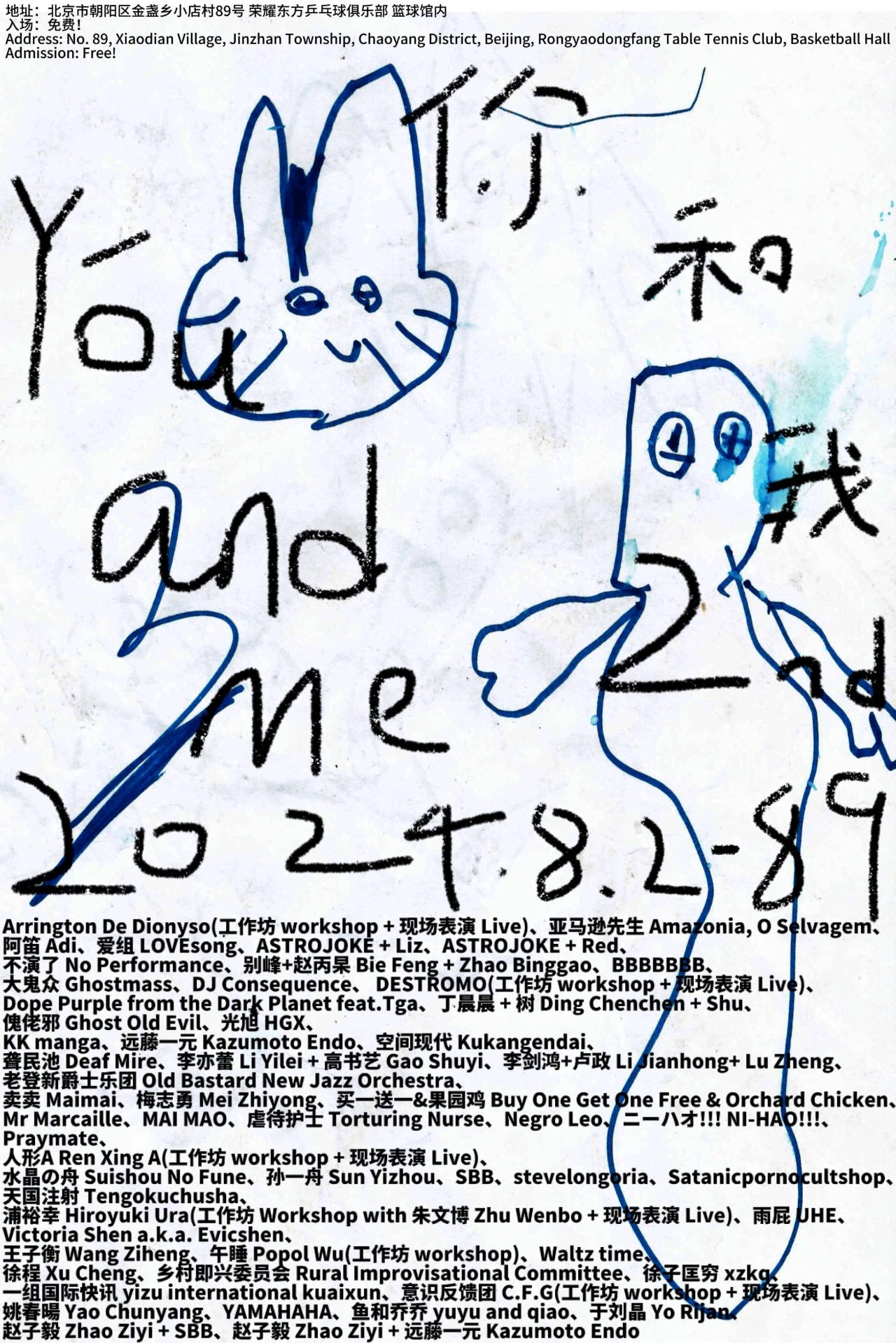

Most music performances face even stricter layers of approval, with complex requirements for both venues and artists. As a result, experimental music events that lack institutional backing or have no chance of passing review often turn to spaces like xiaozu. Zhao Ziyi, who curates xiaozu’s music programming, is something of a cult-legend among Beijing’s new generation of underground musicians. Born in 2007, he not only organizes shows but also performs experimental noise music himself. He also runs a fringe music festival called “You and I,” which invites underground and experimental musicians from around the world.

Film screenings present similar challenges. The approval process for theatrical release in China is notoriously strict, making independent screenings both rare and risky. Xiaozu regularly screens challenging short films by independent directors. One of their long-term projects is the Video Passageway — a dark, narrow corridor filled with second-hand iphone / ipads displaying monthly rotating video works by mainly local performance artists. There is nowhere to sit; viewers must walk slowly into the damp, narrow space. The experience itself becomes a challenge to the senses and to the viewer’s attention span.

三. Songs of Innocence and of Experience

Many people have told us that the atmosphere in China feels completely different after the pandemic. A shift that is subtle, unspoken, but deeply sensed by anyone who lived through that time. People are more distant with one another. Universities and neighborhoods are no longer freely open to the public. The economy is in decline, and fewer people are willing to pay for culture. Post-pandemic Beijing feels more like a ruin. The once-thriving cultural zone around Gulou, filled with clubs and livehouses, has become a commercial park. Aotu Space, a Beijing art space that had been open for ten years, shut its doors. Fruityspace and Raw Material Space, both long-standing venues, are now on the edge of survival. In this context, choosing to open a new space felt almost like trying to build order from the wreckage. What grows in such an environment is bound to be chaotic, peculiar.

Since opening, Xiaozu has encountered nearly every challenge a space in China might face. Beyond tense neighbor relations, they’ve had to navigate various levels of bureaucracy and cultural regulation. Last year, for example, a Halloween screening of The Rocky Horror Picture Show was cancelled, because Halloween gatherings weren’t allowed, and police visited the space multiple times. Xiaozu is located in a district designated as an administrative zone, where commercial activity is quietly discouraged. None of these rules are posted, they’re discovered through trial and error. For instance, we realized the front gate was installed by the government and can’t be altered; the doorplate can’t be too large and must follow the standard 13x8 cm format; signage outside the door is not allowed. Business licenses are also tightly controlled, and it’s not possible to register for food or alcohol sales in the area, meaning Xiaozu must operate with extreme caution. All these compromises stack atop one another, adding weight to an already challenging climate. Since opening, rent and renovations have been fully covered by the four founders themselves, with occasional support from friends. But income from events, space rentals, or drink sales has been far from enough to cover costs.

Even so, the hutongs around Gulou remain one of the best places to run a small culture space. Since the early 2000s, this hutong area has been full of complexity, with rent prices varying widely, refurbished courtyard houses existing alongside narrow, dilapidated single-room dwellings. Locals, "drifters to Beijing”, artists, and foreigners all find refuge here. The close proximity of low-rise buildings creates a unique intimacy, giving the neighborhood its eclectic and open character, and in turn, shaping the feel of the space itself.

It is in this environment that Xiaozu has grown. Even xiaozu’s logo reflects this duality of disorder and elevation: a house that swallows / becomes a head, while also lifting the figure off the ground. A friend once told xiaozu, half-pessimistically, that change requires the sacrifice of each generation’s innocence. And that innocence and cruelty have never truly been opposites. It’s as if the four members of Xiaozu are feeding the space with their own flesh, becoming “the person inside (naka no hito [中の人]),”2 breathing, dancing, living within the space. The house trembles with them. And in the process of growing the space, they too must shed their skins — reworking how they live and relate to others, gaining new experience, and perhaps arriving at a new form of innocence.

The House of Flesh and Ruins — its face blurred, innocent and cruel. In such a limited space, can we truly create “some new work” with boundless possibility? Perhaps the most important role of a place like this is precisely to ask that question on xiaozu’s behalf — just as it is posed in William Blake’s "The Tyger," Songs of Experience:

Tyger Tyger, burning bright,

In the forests of the night;

What immortal hand or eye,

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?In what distant deeps or skies.

Burnt the fire of thine eyes?

On what wings dare he aspire?

What the hand, dare seize the fire?And what shoulder, & what art,

Could twist the sinews of thy heart?

And when thy heart began to beat.

What dread hand? & what dread feet?What the hammer? what the chain,

In what furnace was thy brain?

What the anvil? what dread grasp.

Dare its deadly terrors clasp?When the stars threw down their spears

And water'd heaven with their tears:

Did he smile his work to see?

Did he who made the Lamb make thee?Tyger Tyger burning bright,

In the forests of the night:

What immortal hand or eye,

Dare frame thy fearful symmetry?

Fluid but Unbroken — from Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy: “Though all things flow and shift, life itself remains indestructible — and even delightful.”

The “Naka no Hito” Metaphor: The Japanese phrase naka no hito (中の人), meaning “the person inside,” originally referred to the unseen performer behind a VTuber avatar. Over time, it has come to represent all those who labor behind digital identities, characters, systems, or cultural machines — developers, operators, facilitators, and animators of experience.

*P.S. from the editor:*

What comes out of xiaozu — performance, music, painting, or simply presence — almost doesn’t matter. And that’s exactly what makes it so rare. There’s no tidy aesthetic thesis, no desire to be neatly understood. What they’re doing feels closer to instinct: a raw response to constraint, a refusal to wait for permission. In that refusal, they’ve become something of a mirror — catching the hunger, frustration, and fierce will to create that defines a generation right now, in real time.